The History of Calculus

Date:

‘This is about the history of Calculus’

“The main duty of the historian of mathematics, as well as his fondest privilege, is to explain the humanity of mathematics, to illustrate its greatness, beauty, and dignity, and to describe how he incessant efforts and accumulated of many generations have built up that magnificent monument, the object of our most legitimate pride as men, and of our wonder, humility and thankfulness, and individuals. The study of the history of mathematics will not make better mathematicians but gentler one, it will enrich their minds, mellow their hearts, and bring out their finer qualities.”

The Motivation for the Calculus

Following hard on the adoption of the function concept came the calculus, which, next to Euclidean geometry, is the greatest in all of mathematics. Though it was to some extent the answer to problems already tackled by the Greeks, the calculus was created primarily to treat the major scientific problems of the seventeenth century.

There were four major types of problems.

The first was: Given the formula for the distance a body covers as a function of time, to find the velocity and acceleration at any instant; and, conversely, given the formula describing the acceleration of a body as a function of the time, to find the velocity and the distance traveled. This problem arose directly in the study of motion and the difficulty it posed was that the velocities and the acceleration of concern to the seventeenth century varied from instant to instant. In calculating an instantaneous velocity, for example, one cannot, as one can in the case of average velocity, divide the distance traveled by the time of travel, because at a given instant both the distance traveled and time are zero, and $0/0$ is meaningless. Nevertheless, it was clear on physical grounds that moving objects do have a velocity at each instant of their travel. The inverse problem of finding the distance covered, knowing the formula for velocity, involves the corresponding difficulty; one cannot multiply the velocity at any one instant by the time of travel to obtain the distance traveled because the velocity varies from instant to instant.

The second type of problem was to find the tangent to a curve. It was a problem of pure geometry, and it was of great importance for scientific applications. Optics, as we know, was one of the major scientific pursuits of the seventeenth century; the design of lenses was direct interest for Fermat, Descartes, Huygens, and Newton.

The third problem was that of finding the maximum or minimum value of a function. When a cannonball is shot from a cannon, the distance it will travel horizontally-the range-depends on the angle at which the cannon is inclined to the ground. One “practical” problem was to find the angle that would maximize the range. Early in the seventeenth century, Galileo determined that(in a vacuum) the maximum range is obtained for an angle of fire of 45 degree. The study of the motion of the planets involved maxima and minima problems, such as finding the greatest and least distances of a planet from the sun.

The fourth problem was finding the lengths of curves, for example, the distance covered by a planet in a given period of time; the area bounded by curves; volumes bounded by surfaces; centers of gravity of bodies; and the gravitational attraction that extended body, a planet for example, exerts on another body. The Greeks had used the method of exhaustion to find some areas and volumes. Despite the fact that they used it for relatively simple areas and volumes, they had to apply much ingenuity, because the method lack generality. Nor did they often come up with numerical answers. Interest in finding lengths, areas, volumes, and centers of gravity was revived when the work of Archimedes became known in Europe. The method of exhaustion was first modified gradually, and then radically by the invention of the calculus.

The Seventeenth-Century Work on the Calculus

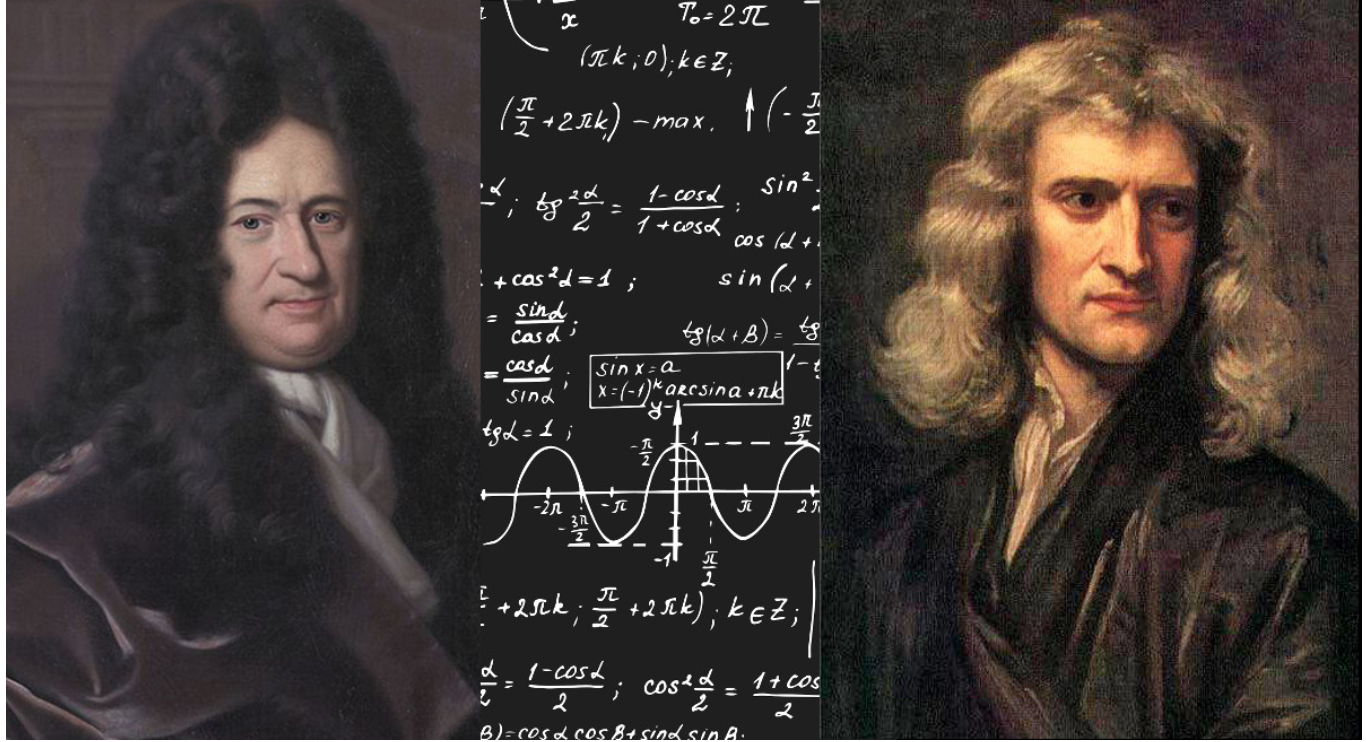

The problems of the calculus were tackled by at least a dozen of the greatest mathematicians of the seventeenth century and by several dozen minor ones. Sir Isaac Newton was a mathematician and scientist, and he was the first person who is credited with actually developing calculus. It really is an incremental development, and many other mathematicians had part of the idea. In fact, Newton’s teacher, by the name of Barrow, actually said “the fundamental theorem of calculus” in his writings but somehow didn’t realize the significance of it and didn’t actually highlight it. But he was Newton’s teacher and presumably Newton learned things from him. Fermat invented some of the early concepts associated with calculus, finding derivatives and finding maxima and minima of equations. And other mathematicians, many mathematicians contributed to both the development of the derivative and the development of the integral. All of their contributions were crowned by the achievements of Newton and Leibniz. Here we shall be able to note only the principle contributions of the precursors of these two masters.

The discovery of calculus is often attributed to two men, Issac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz, who independently developed it foundations. Although they both instrumental in it creation, they thought of the fundamental concepts in very different ways. While Newton considered variable changing with time, Leibniz thought of the variable $x$ and $y$ as ranging over sequences of infinitely close value. He introduced $dx$ and $dy$ as differences between successive values of these sequences. Leibniz knew that $\dfrac{dy}{dx}$ gives the tangent but did not use it as a defining property. One the other hand, Newton used quantities $x’$ and $y’$, which were finite velocities, to compute the tangent. Of course neither Leibniz nor Newton thought in terms of functions, but both always thought in terms of graphs. For Newton the calculus was geometrical while Leibniz took it towards analysis.

It is interesting to note that Leibniz was very conscious of the importance of good notation and put a lot of thought into the symbols he used. Newton, on the other hand, wrote more for himself than anyone else. Consequently, he tended to use whatever notation he thought of on that day. This turned out to be important in later developments. Leibniz’s notation was better suited to generalizing calculus to multiple variables and in addition it highlighted the operator aspect of the derivative and integral. As a result, much of the notation that is used in Calculus today is due to Leibniz.

The development of Calculus can roughly be described along a timeline which goes through three periods: Anticipation, Development, and Rigorization. In the Anticipation stage techniques were being used by mathematicians that involved infinite processes to find areas under curves or maximaize certain quantities. In the Development stage Newton and Leibniz created the foundations of Calculus and brought all of these techniques together under the umbrella of the derivative and integral. However, their methods were not always logically sound, and it took mathematicians a long time during the Rigorization stage to justify them and put Calculus on a sound mathematical foundation.

In their development of the calculus both Newton and Leibniz used “infinitesimals”, quantities that are infinitely small and yet nonzero. Of course, such infinitesimals do not really exist, but Newton and Leibniz found it convenient to use these quantities in their computations and their derivations of results. Although one could not argue with the success of calculus, this concept of infinitesimals bothered mathematicians. Lord Bishop Berkeley made serious criticisms of the calculus referring to infinitesimals as “the ghosts of departed quantities”.

Berkeley’s criticisms were well founded and important in that they focused the attention of mathematicians on a logical clarification of the calculus. It was to be over 100 years, however, before Calculus was to be made rigorous. Ultimately, Cauchy, Weierstrass, and Riemann reformulated Calculus in terms of limits rather than infinitesimals. Thus the need for these infinitely small (and nonexistent) quantities was removed, and replaced by a notion of quantities being “close” to others. The derivative and the integral were both reformulated in terms of limits. While it may seem like a lot of work to create rigorous justifications of computations that seemed to work fine in the first place, this is an important development. By putting Calculus on a logical footing, mathematicians were better able to understand and extend its results, as well as to come to terms with some of the more subtle aspects of the theory.

When we first study Calculus we often learn its concepts in an order that is somewhat backwards to its development. We wish to take advantage of the hundreds of years of thought that have gone into it. As a result, we often begin by learning about limits. Afterward we define the derivative and integral developed by Newton and Leibniz. But unlike Newton and Leibniz we define them in the modern way – in terms of limits. Afterward we see how the derivative and integral can be used to solve many of the problems that precipitated the development of Calculus.

The Controversy Between Newton and Leibniz

The controversy between Newton and Leibniz started in the later part of the 1600s. 1699 was a date associated with a start of a tirade, which just went downhill. It was a tremendous controversy. But Leibniz had this to say about Newton. And I’ve served on many committees reading letters of recommendation for mathematicians, you know, for positions, and I can assure you that there are huge numbers of mathematicians who are the best three mathematicians in the world in any given field, but if a sentence like Leibniz’s sentence on Newton appeared in a letter, one would take notice. Leibniz said about Newton, “Taking mathematics from the beginning of the world to the time when Newton lived, what he has done is much the better part.” This was Leibniz talking about Newton.

But when Newton began to realize that Leibniz had the ideas of calculus, which he began to realize in the 1770s, Newton’s response to make sure that he got credit for calculus was to write a letter to Leibniz in which he encoded a Latin sentence and I will—well, I won’t attempt the Latin, but I’ll attempt just a few words of the Latin. It starts out, “Data aequatione quotcunque” and so on. It’s a short Latin sentence whose translation is, “Having any given equation involving never so many flowing quantities, to find the fluxions, and vice versa.” This was a sentence that encapsulated his, Newton’s, thinking about derivatives. And what he did is he took that sentence and he just took the letters, individual letters, a, c, d, e, and he put them just in order. He said there are six a’s, two c’s, one d, 13 e’s, two f’s. He put them in order and that was what he included in this letter to Leibniz to establish his priority for calculus. And I read you the sentence, which means very little to anybody. Even a mathematician wouldn’t know from the actual translation of the sentence exactly what it was that he had done.

So he tried to establish his priority in that fashion, but then there were accusations that Leibniz had read some of these manuscripts of Newton’s work before he got the ideas. But since Leibniz had published first, people who were siding with Leibniz said that Newton had stolen the ideas from Leibniz. And it was a huge mess, which incidentally led to British mathematics being very retarded for the next century because they didn’t take advantage of the wonderful developments of calculus that were taking place on continental Europe.

Keep Reading

如有侵權,請立即告知。 Please advise to remove immediatly if any infringement caused。